Volver a actualidad | Ver todas las noticias | Ver todas las actividades

Montreal - 08/01/2013

Publicada: 08/01/2013

Dr. Norman Bethune is Canada’s most well-known volunteer in the Spanish Civil War David Rodríguez Solás. Alba Volunteer, 04-01-2013

Remembering Bethune in Málaga and Montréal

Dr. Norman Bethune isCanada’s most well-known volunteer in the Spanish Civil War

January 4, 2013

The recent popularity of public commemorations of violent events from the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship has rubbed some academic historians the wrong way. “We’ve known about these events for years,” they say. “We’ve written dozens of books and articles about them. We know almost all there is to know about the repression. And these ‘recoveries of historical memory’ are often not historically accurate.”

They are not wrong. The problem is that the impact of academic work tends to be very limited. If the general public inSpainlearns about local histories of the repression, it is through family stories or other non-academic venues: the press, documentaries—and yes, commemorative events that seek to “recover historical memory.” Even the impact of a book like Paul Preston’s The Spanish Holocaust, which is written for a general readership and appeared in Spanish translation one year before it was published in English, will ultimately be limited.

Still, the tremendous rise of non-academic accounts about the past poses a problem. How do we judge their legitimacy in terms of truth and accuracy?

These were the questions I asked myself in 2009, when I saw an exhibition at the McCord Museum of Montréal, the city where I lived and worked at the time, about Dr. Norman Bethune. Bethune isCanada’s most well-known volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. As head of the Canadian Medical Unit inMadrid, he introduced a revolutionary method for blood transfusions. The year 2009 marked the 70th anniversary of his death. He passed away in1939 inChina, while serving as a doctor in Mao’s army. (The Chinese have long revered Bethune as a national hero.)

The Montréal show opened first in Málaga in 2004, where it was visited by ten thousand people. Both exhibits consisted of 56 photographs and text panels that documented Bethune’s career and focused in particular on his role during the tragic evacuation of Málaga in February 1937. Following a ruthless occupation of the city, the Nationalists savagely attacked the thousands of refugees on a desperate trek along the coastal road from Málaga to Almería, an event that has become known as “The Crime of the Road to Málaga” (el crimen de la carretera de Málaga). (I have to admit that all I knew about this episode at the time was based on the stories told to me by my grandmother, who fled her hometown of Marbella in February 1937.)

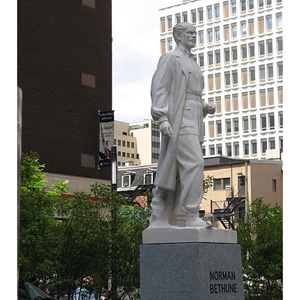

The Montréal exhibition was so successful that it was extended twice. And yet the focus of the show was unusual. InCanada, Bethune’s life is not often associated with his Spanish years. The only statue of the doctor in Montréal was a 1976 gift from the Chinese government, and depicts him with the clothes he wore during his years inChina. Similarly, Bethune’s Asian ties are often brought to the fore by Canadian authorities when they are interested in strengthening their commercial connections withChina. In contrast with the successful photo show, the official tribute to Bethune in Montréal drew a very small attendance—admittedly, it was a cold day—and was all but ignored by the local media. Still, the city had ambitious plans to honor him with an eighteen-month series of events that included rebuilding theNorman Bethune Squarein Montréal.

This lack of official interest in Bethune’s volunteer work inSpainis not coincidental. Canadian authorities and institutions have not been particularly keen to commemorate their country’s role in the Spanish Civil War. As the Volunteer has reported, for instance, there will be no official commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the creation of the Mackenzie-Papineau battalion. Michael Petrou was right when he wrote in his book Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, that the history of the Canadian volunteers inSpainis still largely neglected.

In fact, in some sense the adventurous life of Norman Bethune, who paradoxically did not serve with the “Mac-Pacs,” may have eclipsed the stories of other Canadian volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. This is certainly true in the case of Hazen Sise, a member of the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit. When Bethune recruited him inLondonas an ambulance driver, Sise was a prominent architect from Montréal who had worked with Le Corbusier and collaborated with László Moholy-Nagy. It was Sise who took the photographs included in The Crime on the Road Málaga-Almería, Bethune’s well-known pamphlet on the attack of the Málaga refugees. The photographs are stunningly powerful—it is clear they were taken by a visual artist.

Sise himself later recorded his memories of the evacuation as part of an oral history project at theUniversityofWestern Ontario. From his account we learn that the Canadians’ trip toAndalusiawas in fact a matter of chance. InBarcelonathey decided to try Dr. Durán-Jordà’s system of refrigerating blood in different places; thus they planned to drive to Almería, from there to Málaga, and later to return toMadrid. But “when we came into Almería,” he recalled, “it was obvious that something was up. The town seemed to be in a state of panic.” It didn’t take them long to learn why: “We began to run into this bedraggled procession of people by twos and threes at first and then gradually thickening into a great swarm.” They decided to continue regardless, although it was “very much like driving in a blizzard inCanadaand the snowflakes come at you in the windshield and in the headlights. And we drove through burning villages and it reminded [me] so much of the battle pictures in Napoleonic times—these half-ruined burning farmhouses and things and troops streaming through and people in panic streaming through.”

What Sise and his fellow Canadians saw from the road was a traumatic image that accompanied them for the rest of their stay inSpain. Back inMadridseveral months later, Sise recalled the episode in one of his radio addresses forNorth America, which the Canadians transmitted three times a week from EAQ, a small station off Gran Vía. He still had this “heartrending sight” in his mind: “women carrying children, small children carrying even smaller children; the father, if he hadn’t already died during the last desperate week, carrying a few hastily gathered personal effects.”

Surprisingly, the figure of Norman Bethune and the members of the Canadian Blood Transfusion were almost completely unknown to the people of Málaga in 2004, when the exhibition on Bethune opened. “Norman Bethune. El crimen de la carretera Málaga-Almería (febrero 1937)” featured the twenty-six pictures by Sise that had first appeared in Bethune’s pamphlet. It was part of a series of events planned by Málaga’s provincial government to commemorate the exodus of the estimated 120,000 to 150,000 refugees who walked the more than200 kilometersto Almería. Other events included Rogelio López Cuenca’s installation and companion web site “Málaga 1937. Nunca más” (www.malaga1937.es), which contained oral testimony and reproductions of related documents from the time. Professors Lucía Prieto Borrego and Encarnación Barranquero Texeira were commissioned to write a monograph published by the provincial government in 2007, Población y guerra civil en Málaga: caída, éxodo y refugio (The Population of Málaga during the Civil War: Fall, Exodus, and Refuge). Both the installation and this book included conspicuous testimony from survivors who were identified as the protagonists of the events and placed in the spotlight.

Interestingly, the exhibition in Málaga, which later traveled to Montréal, fully adhered to the narrative of the event as it was first presented in Bethune’s writings. Even the testimonies included had clearly been selected and edited to confirm that version. This is surprising, because The Crime on the Road Málaga-Almería was a pamphlet aimed at a North American audience, meant to persuade them to support the Republic. Originally written in English in 1937, it was also printed in French and Spanish. The text accompanying the pictures was a shorter version of the journal Bethune logged in Almería after his experience. It was indeed a calmer reflection on the events, but one that could still be used for propagandistic purposes.

In the pamphlet, images and text shared central stage. Subtitled “A Narrative with Graphic Documents Revealing Fascist Cruelty”, the pamphlet included all the pictures taken by Sise. Their striking captions are perhaps the most genuine propagandistic element of this leaflet: they deliberately aimed to shape the viewers’ reactions by evoking their emotions. In one particular case, the only contextualization of a cropped figure of a child is the caption. All we see is the child, with her back turned, standing by a broken doll. Almost all the context needed for our interpretation is provided by the caption: “Abandoned? Lost? The girl’s suffering is such that she forgets or ignores her treasure from the day before” (“¿Abandonada? ¿Perdida? La niña sufre hasta el extremo de olvidar o desdeñar su tesoro de ayer”). Bethune’s text, too, underscores the suffering of innocent children. He asserts there were more than five thousand of them on the road, of whom a thousand were walking barefoot. These hyperbolic accounts abound in the text—logically so, given the pamphlet’s context and purpose.

Surprisingly, these captions were uncritically included in the Málaga exhibition 67 years later, reproducing the hyperbole and lack of context we see in the pamphlet. Furthermore, the original photographs and captions were accompanied by additional texts that reinforced this initial interpretation. A woman refugee by the name of Dolores Vázquez, for instance, recalls that when she lost sight of her parents in the melee, “I started to cry, calling for them. I was terrified. I had no energy left to walk any further, I was lost.” By featuring only the voices of the witnesses, Jesús Majada, curator of this exhibition, hindered visitors’ hopes to have a more complete understanding of the facts behind the tragic event. How was life on the road? Did the refugees know where were they going? What happened to them after they arrived in Almería? I asked myself these questions, too; but for the answers I had to go Prieto Borrego and Barranquero Texeira’s book. As it turns out, despite what some of Sise’s pictures show, it seems that most of the refugees fled without carrying much of their belongings. They certainly did not know their destination, which was not Almería for some of the survivors, butValencia,Barcelona. Like other republican refugees, some of them eventually made it as far asMexicoorChile.

The purpose of Bethune’s pamphlet was obvious enough. But what was the purpose of the exhibit? Clearly not to present an unbiased presentation of the events that took place on the road from Málaga to Almería. But while the compassion and anger that Bethune sought to evoke had a clear political consequence—to help theSpanishRepublic—the same is not true for the exhibit. The pictures and the pamphlet have undeniable value: they provide unique evidence of the ruthless experience of the victims. But to revive them uncritically seven decades after the fact is counterproductive. The audience would have benefited much more from conventional explanatory panels side by side with the testimony of the survivors. The exhibition, in other word, was a missed opportunity—in terms of education, in terms of history, and also in terms of the so-called recovery of historical memory.

David Rodríguez Solás is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Spanish atBardCollege. He has just published the article “Remembered and Recovered: Bethune and the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit in Málaga, 1937″ in the Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos.

http://www.albavolunteer.org/2013/01/remembering-bethune-in-malaga-and-montreal/

FORO POR LA MEMORIA HISTÓRICA DE MÁLAGA

Teléfono de contacto: 665 91 75 83 - E-Mail: recuperandomemoria@gmail.com